Veiling and Unveiling

Fifth Sunday of Lent. Fr Richard Ounsworth explores the ironies of today’s liturgy.

There are two strange ironies in today’s liturgy. First, as we enter the last two weeks of Lent, traditionally called ‘Passiontide’, and turn our minds in a special way to the suffering and death of Christ, it’s slightly odd that all the readings should be about Resurrection. Secondly, if we’re supposed to be thinking especially about the Cross, isn’t it strange that today is the day when all our crosses and crucifixes are covered up?

It’s really not a bad idea, though, to cover them for a couple of weeks. We see crosses and crucifixes so often, not just in church but in art and in jewellery and everywhere we look, that it’s very easy to stop noticing them. One of the central themes of St John’s Gospel is that of Christ on the Cross like a lantern lifted up high in the darkness for everyone to see; yet the image of the crucifixion is so common in our benighted society that scarcely anyone gives it even a glance.

But the death of Christ, and the kind of death he died, is so appalling, horrific and grotesque that we ought to be shocked by it. We should be stunned into speechlessness at the thought that the Lord of the Universe, the Creator of the World, Word-made-flesh and Splendour of the Father ended his ministry of love choking out his last agonised words on a Roman cross.

So perhaps it’s part of the wisdom of the tradition of the veiling of images that we are given time to become un-used to the crucifixion. In a peculiar way, the covering of the cross helps us to see it properly again, not as a fashion item, nor indeed as a highly successful piece of branding by the Christian Church, but as the awful reality of the saving love God showed us in his Son.

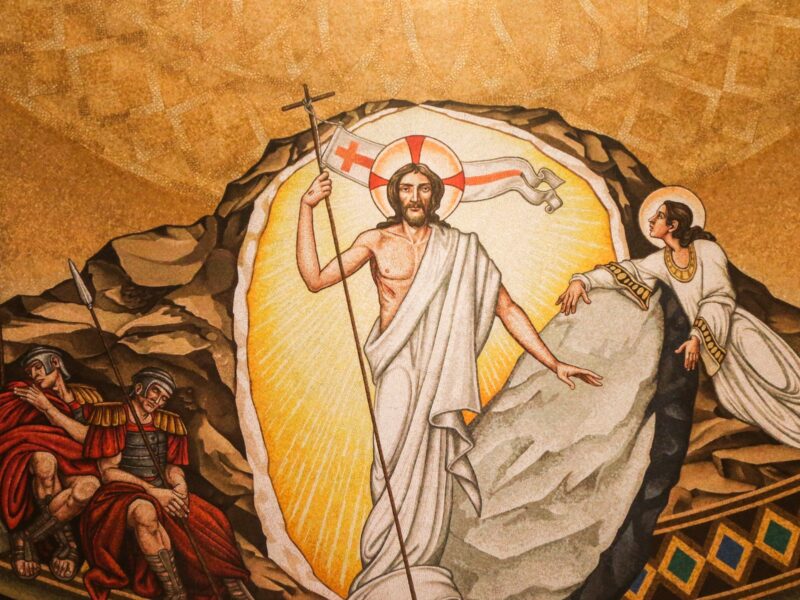

And maybe it’s the renewal of this shock that leads the Church to give us today’s readings about resurrection: just as when Jesus first told his disciples of his own approaching death, he gave them the consolation of the transfiguration, so now when we learn again the truth of how God took upon himself the true pain of the sins of the world, we also receive the reminder that sin and pain and death do not have the last word. Rather, God has the last word; and as his first word was the word of creation, so this last word is a word of re-creation and new life.

This doesn’t mean that death is nothing at all, something we can just shrug off. Jesus wept at the death of his friend Lazarus, and at the sorrow that his death caused to those who loved him. Death is no illusion; but for us who are Christ’s friends, death is not the end of the story, but the beginning of the last and most glorious chapter of our life stories. Not just an awkward interruption in our lives, death — the disastrous result of human sin — has been transformed by God into the gateway to an utterly new kind of life.

This is the new life of Christ’s resurrection. The abandoned grave clothes left behind in Jesus’s empty tomb had fallen away from a man born again, while the garments stripped from Lazarus’s body only left him free to resume the life he had begun many years before. Out of his love for Lazarus, the Lord called him out of the tomb to take up again the life of friendship with Christ; and as we go on to discover at the beginning of the next chapter, Lazarus’s life is now in danger because of his relationship to Jesus, so he has been brought out of his tomb to walk again in the shadow of death.

Whereas he has called us out of the darkness to walk in newness of life. In baptism, we were clothed again not in the garments of death but in the life-giving Christ. The veil has been taken from our faces so that we can see more clearly than ever. When we unveil our crosses on Good Friday, we will be able to look at the image of our Saviour in his agony and see God’s love for us shining through the face of Jesus.