Blessed are the Poor in Spirit

Fourth Sunday in Ordinary Time (A) | Fr Richard Finn asks who are the “poor in spirit” and what is meant by calling them “blessed”.

Who on earth are the ‘poor in spirit’? These words of Jesus may puzzle us. They have no ready parallel in the Old Testament. Nor would any pagan reader of Matthew’s Gospel in the late first century have understood this strange term. Who on earth will inherit the kingdom of heaven?

As Christians, long familiar with the Gospels, we may think we have the answer – it’s humility, isn’t it? The uniquely Christian virtue missed by the ancient philosophers, the ‘wise’ who, St Paul tells the Corinthians, are shamed by God’s choice of ‘those whom the world thinks common and contemptible’. But while this is true, it may not get us far. What is the humility which Jesus here pronounces blessed?

We won’t find an answer if we think Our Lord goes on to announce a series of disparate rewards for disparate characters: one thing for gentlefolk; another thing for mourners; for those moved at the plight of the oppressed; for the innocent of heart; and so on. What, though, if Jesus here pronounces God’s one blessing, not on this or that group of people, but on His one people, His Church, as they remain faithful to His calling and mission? Christian humility will be a life that is marked by mercy rather than retribution, endurance even under persecution, gentleness, and the resolute search for peace and justice made possible by innocence of heart.

What Jesus teaches in the beatitudes is in fact the way of life that He Himself already lives by the power of the Holy Spirit. We shall understand how that power enables a certain kind of poverty when we reflect on the Divine Pity that took on flesh and suffered for love of sinners. This is the humility that thinks no discomfort, no hard truth, too high a price for the dignity of others. Humility gets its hands dirty, gets down on hands and knees if need be, so that others can stand tall. This is the humility of the prophet, the healer, the man or woman of persistent prayer.

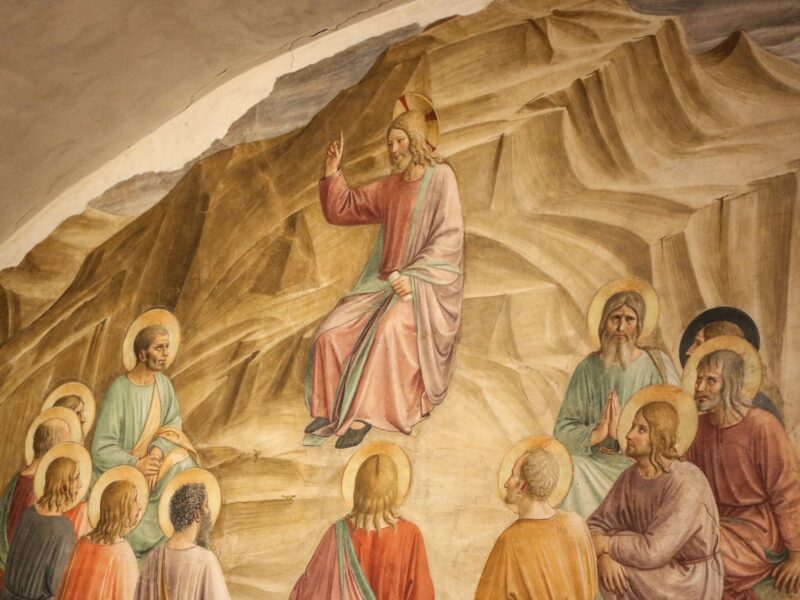

This episode in Gospels recalls how the hidden God once spoke to Moses from the cloud over Mount Sinai. God then gave Moses the commandments, a way of life and freedom for Israel. What we have here isn’t a replacement for that way of life. Jesus tells us, rather, what that life costs in an evil world, and so how God blesses us for our fidelity to that way of life. In this sense, it looks forward to the cross and to the resurrection of Christ. The beatitudes assure us that as we share in His Passion, so shall we also share in His resurrection to eternal life.

It’s surely best, then, not to translate these beatitudes by ‘Happy are ’. Those who are cursed and persecuted are rarely happy about it (and if they really enjoyed it, would you want to share eternity with them?). Those who mourn cannot be happy now by definition. Let’s not gloss over the hardship to be endured by virtue of God’s present blessing. Indeed, it is precisely God’s blessing that is the well-spring of our hope.

God spoke and it came to be. God’s word is always creative of what it promises. To be blessed by God is to be given new life, graced, enabled for this life of discipleship, and made ready to enjoy the final and lasting bliss of heaven, that kingdom where we shall know only the love of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. This is why the great African theologian, St Augustine of Hippo, matched up the beatitudes with the effects of the Holy Spirit foretold by Isaiah. Our Gospel announces the life of grace. The same divine charity both makes for the life of the virtues in adversity and for the life of glory in eternity. One blessing, one reward if you like, for the one way of life.

And yet the Church Fathers also saw a kind of progression within the beatitudes, saw them as building one on another. It takes a certain foundational humility to accept the message of Gospel, its warning that sin brings death, of our urgent need for salvation. And there is no conversion of life that does not entail sadness, sorrow for sin and the pain of detachment. From these come that gentleness which remembers ours own moral weakness as we serve others in the Christian life. We cannot secure the peace which results from a just order and friendship if our hearts are skewed by injustice, distracted by selfish ambitions careless and destructive of the common good. The different virtues combine to form a unity.

Why, though, so many different promises for what is ultimately the one reward? It matters that Our Lord promises to satisfy those who hunger for justice, comfort for those who mourn: suffering, though real, is redeemed, healed or redressed. When the merciful receive mercy, they in some sense receive what they forwent. If we are to sacrifice real human goods, we must know that this is not ultimately at the expense of our humanity. But other promises tell of God’s extraordinary gift of a more than human nature, our entry into the Triune life of God by adoption in Christ, to become heirs with Him of the Father. The different promises reveal all that we hope for in Christ. By sharing in His humility we hope to share in His divine glory.

Zeph 2:3; 3:12-13 | 1 Cor 1:26-31 | Matthew 5:1-12

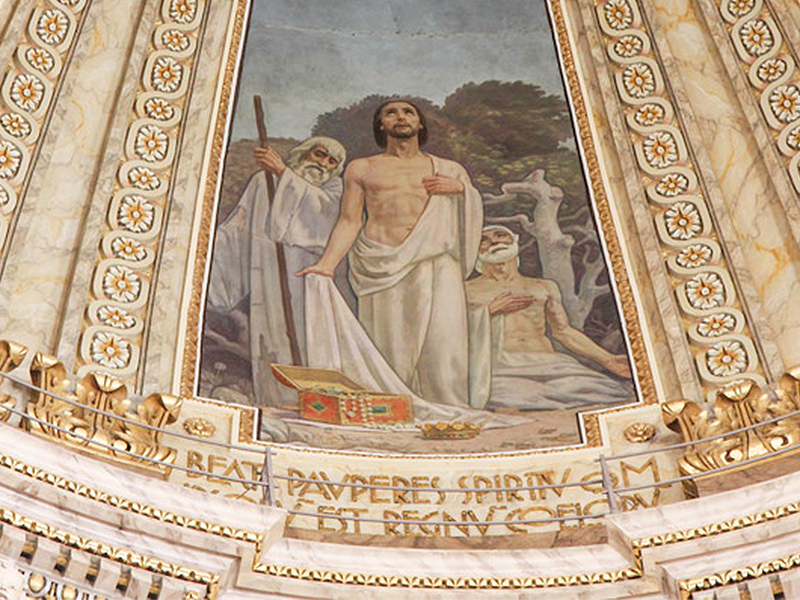

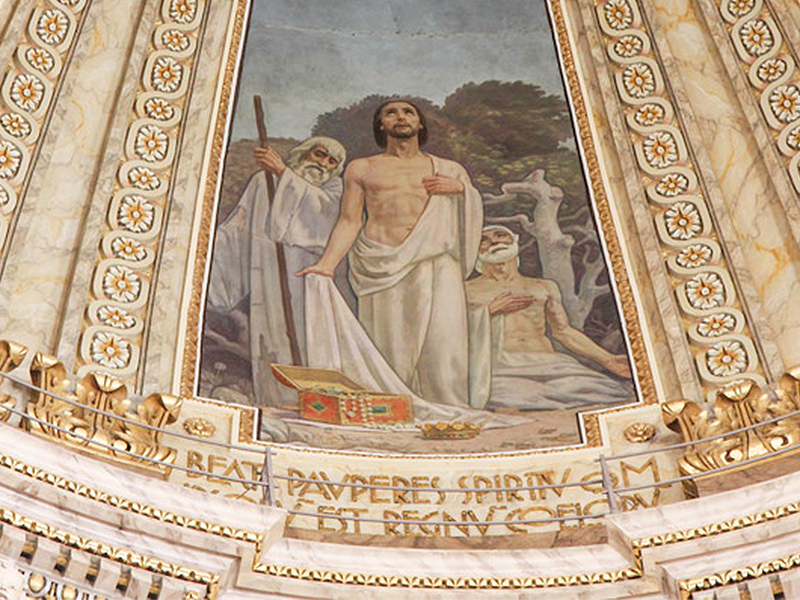

Photograph by Fr Lawrence Lew OP of a ceiling in the church of St Paul, Rabat.