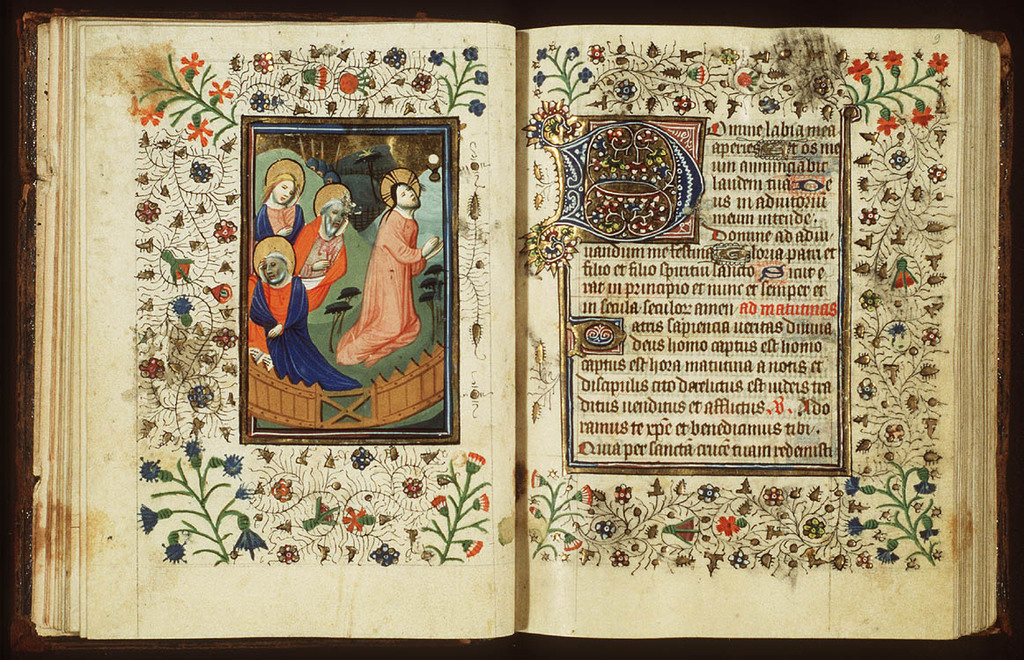

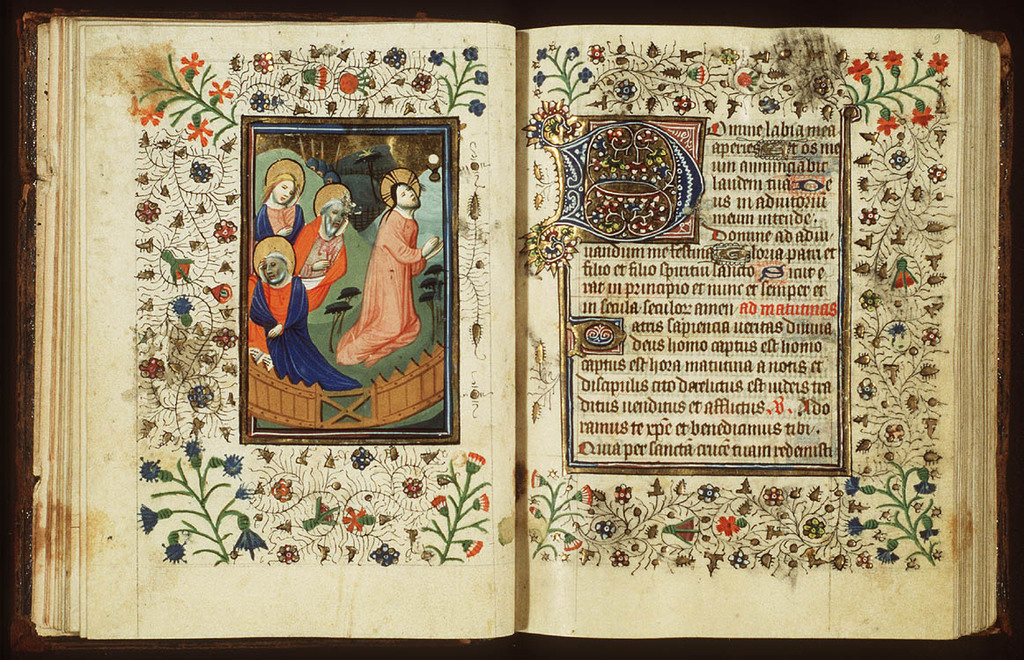

Our Lord Jesus Christ, Eternal High Priest

St Paul teaches that Christian worship is ‘wordy worship’: this, Christ models for us by his priestly prayer in Gethsemane.

Reading: Genesis 22:9-18; Psalm 39(40):7-10, 17; Matthew 26:36-42

The following homily was preached to the student brothers during compline. You can listen here or read below:

We often put up words as smoke and mirrors. We use language to obfuscate and obstruct, as a barrier to protect ourselves – sometimes understandably – from feared violence, be that the violence of other people’s scrutiny and demands, the violence perhaps of impositions and lies, sometimes even the violence of truth. The diffident among us multiply words to defer getting to the nub of the matter, the crisis that occurs when we spit it out and say what we mean. Concealments and carefully constructed answers enable us to elude and evade responsibility. When Abraham is asked by Isaac, ‘what are we going to sacrifice?’, the old man misdirects: ‘God will provide’, he says. The words prove to be prophetic, but not because of Abraham’s honesty.

Isaac’s question, by contrast, cut to the heart of the matter. These were words that exposed his innocence and vulnerability: when he speaks them, we all know what is in Abraham’s heart to do. It is striking, on the feast of Christ the High Priest, that in this episode the foreshadowing figure of Jesus is not Abraham, the sacrificer, but Isaac the innocent son and the ram that is in the end the sacrificial victim. And the Gospel of this day presents Christ in Gethsemane, modelling for us a language of surrender and vulnerability: not my will, but thine be done. The Psalm, too, gives us those frighteningly unqualified, even naïve words: ‘Here I am, Lord! I come to do your will’. This is the other way that words may take: exposure, putting oneself at another’s disposal, bearing one’s heart that it might reach through to heart.

Christian worship, Christian sacrifice, is what St Paul calls a ‘wordy worship’, logike latreia (Rom. 12.1): it’s an unusual expression, and almost never translated that way, but that’s what the words literally mean. Contained in that enigmatic expression are several thoughts: worship in the Word who is Christ, worship by the homage of words, the worship that is proper to a rational animal – which is to say, a language animal. For words are just the way we pledge ourselves, mundanely and intimately: ‘yes’ to this or ‘no’ to that, saying sorry, saying ‘I forgive’, contracting a marriage, making a vow, professing our faith. The words have to be backed up by action if they are sincere, but the meaning of the action is configured by the words. That’s why it matters to get married: it sets the tone for a couple’s cohabitation, frames their common purpose and holds them accountable to their love for one another – the words safeguard fidelity beyond the convenience and emotions of the moment.

When a priest celebrates Mass, it’s the words that direct us to Christ’s memory, Christ’s words that make us really present to his once-for-all sacrifice. Fr John Harris on Sunday spoke to us of Pentecost as an event happening in the present continuous tense: Pentecost still happens whenever Christians are born by baptism, strengthened by confirmation, purified by prayer and penance or built up by preaching and by charity. Christ’s priesthood, too, is exercised in the present continuous. His eternal priesthood is the invisible anchor in the life of God on which we tug with every prayer, every offering, every eucharist. Every Christian, by virtue of baptism, each in his or her own way, shares in that priesthood; every Christian tugs on that anchor and pulls the world a little closer to heaven in countless ways.

The liturgy plays out this relationship through the interplay of office and mass. One very important way we exercise this priesthood of language, is in reverent reading and recital, making our own the words of Scripture. By taking Scripture on our own lips, we tell the story and act out the role of Christ’s body on earth. We friars worship in the Psalms at set hours of the day, to make the connection between words and history, to enmesh our biographies in the biography of the whole Christ, the Church. But each day the Mass, and the ministerial priesthood, put us in touch with the eternal, once-for-all offering that gives value and makes sense of these many offerings scattered throughout the course of time. In the Mass, we are reminded of the eternal identity of Christ behind the earthly biography of his body.

Christ’s resolution in Gethsemane, to do the will of his Father, to make himself the lamb of sacrifice, shows for us the kind of real-world decision that affirms this eternal identity. We ourselves haven’t, without grace, the mastery of self to make such a perfect or sincere offering. So we always have to beware the danger of faux piety, the arrogance of Pharisaism – one of the worst sins, because it shields us from the truth about ourselves by putting up a screen of pious platitudes. A major part of our Gethsemane is the confession of our sinfulness. But we only realise our sinfulness sufficiently to confess it when we can confess God’s mercy also. The words the Church gives us in prayer and Scripture are words that habituate us to the tones and melodies of the redeemed: so that the searing sacrifice involved in self-knowledge may be simultaneously praise and worship of God. In these words we expose ourselves to judgment, for what we are, and expose ourselves to a truth that promises to transform us. St Bernard of Clairvaux used to pray: ‘God, come to me as grace and as truth: as truth, that I may not be able to hide; as grace, that I may not wish to hide’.

Image: An illuminated manuscript (1430) of Master of Otto van Moerdrecht, housed in the National Library of the Netherlands, showing Christ’s Agony in the Garden opposite prayers of the Church. In the public domain, courtesy of Picryl